Basso Continuo (or thoroughbass) is a well-known term for regular listeners of Baroque music. But, what is actually meant with it, and where does it originate from?

Imagine being organist in a big church in Italy, around the year 1600. Composers tend to write for ever increasing ensembles. It can happen that a piece for twelve-voiced choir appears on your music stand. As an organist, you are facing the task to accompany such a composition, which, of course, is quite impractical, because you have to read twelve parts at the same time. Moreover, it would require a lot of precious paper. A simple solution for this is needed.

The observation is quickly made that many compositions can be considered as a sequence of chords. What if you would only write down those chords? That would save an enormous amount of work. But then one problem is left. The bass tone is very important. Playing another bass note than the one the choir is singing would violate the composition. So, the final solution is to only notate the bass notes together with indications for the cords. This is the very principle of Basso Continuo. Next to organ accompaniment in churches, this principle was also applied in secular music, for example in operas, or in sonatas for solo instruments.

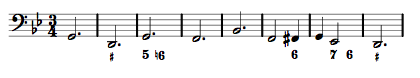

In the seventeenth century, this way of accompaniment became standard, only to disappear at the end of the eighteenth century. Even composers didn’t take the effort to write all notes of the accompaniment. This was considered the task of the performer. He was expected to make up something intelligent above the bass line, based on the chord indications. These cords are denoted with figures. Hence, this notation is also known as figured bass. These figures indicate which notes the player should use in any case. It could, for example, look like this:

Example Basso Continuo - Corelli, La Fiolla

A continuo-player could make this of it: (mp3 – source). This is the accompaniment for La Follia by Arcangelo Corelli, as realized by harpsichord player Richard Egarr. As soon as the violin enters, Eggar reduces the number of notes he is playing, providing a more discrete realization of the same bass line: (mp3 – source).

Often, a continuo part is performed by two instruments: a bass instrument and a chordal instrument; for example, a harpsichord and a cello, or an organ and a bassoon, etc.

Aanbevolen cd’s en dvd’s

Details: Amazon.com or Emusic.com